Whitney Biennial 2017

03/17/2017 Modern & Contemporary Art

When the Whitney Museum reopened in its new location in 2015, it established a new level of excellence for museum architecture (no slight to the great Marcel Breuer intended). The 2017 edition of its famed (and often controversial) Biennial, the first in its new home, was awaited with a similar level of expectation. What is shown across two-plus floors does the new museum proud, and better yet, offers one of the program's more successful iterations in recent memory. Employing the new building’s fantastic available spaces with great care, the exhibit avoids many of the mistakes of Biennials of the past, and at the least is neither overstuffed nor claustrophobic.

Including three elder states-people among its roster of young (and young-ish) artists, the Biennial features abstract painter Jo Baer, minimalist Light and Space artist Larry Bell, and revered conceptual/performance artist William Pope.L. As a survey of Contemporary Art, an issue I (and others) sometimes had with Biennials past was the seemingly unnecessary inclusion of well-established artists from previous generations. Though these three artists have indeed had notable careers, they are far from household names, and are very much alive and still producing important Contemporary Art. In short, they're relevant, and warrant inclusion. Additionally, I'd propose that their inclusion also presents them as tent poles of a sort for their respective mediums, holding the umbrella in which other artists included here fall under -- Baer with painting, Bell with new materials, and Pope.L with conceptual/installation pieces. While much will be discussed about the thematic curation of the Biennial, the space and attention given to paintings here is important, and presenting Jo Baer as painting's champion, at least for this exhibit, is prescient. Similarly, Larry Bell deserves major museum praise for his sublime minimalist sculpture, as does Pope.L for his maddeningly brilliant genre-defying work.

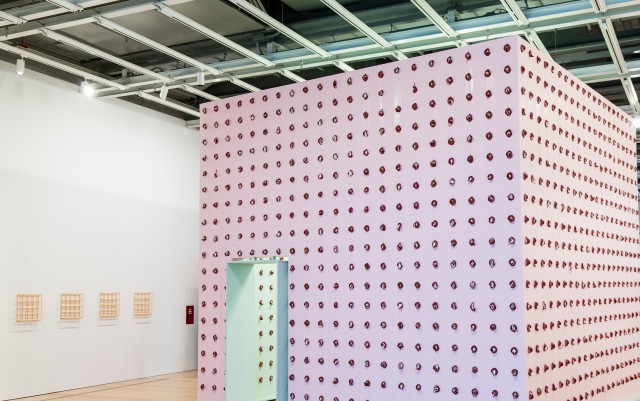

Entering the fifth floor (most of the Biennial shares this and the sixth floor), I was immediately drawn to the strange pink structure covered with little disks to my right. An installation by William Pope.L, entitled Claim, the disks in question are actually 2,755 individual slices of bologna. Each slice features a portrait that Pope.L claims represents a Jewish resident of New York. Reading his typed statement inside, covered in crudely penned annotations, the full intention of the piece seems purposefully obtuse, as does much of his work -- though what I came away with more that anything was the sweet odor of decay. The bologna, he explained, would "weep" throughout the life of the installation, and while that level of rot had not as yet set in, I found myself curious to see and smell what this piece might be a few weeks from now. Odor as a medium isn't one I often consider.

Frances Stark contributed a near roomful of large-scale paintings, each re-appropriating pages from Censorship Now! by author Ian Svenonius. I may be in the extreme minority here, but this was an amazing moment of nostalgia -- the brilliantly strange Ian Svenonius fronted a favorite post-punk band of my youth, the relatively obscure Nation Of Ulysses, whose aggressive, intelligent music was socio-politically confrontational in ways so many bands of their era (and many before them) never had the chops or the smarts to be: smash-the-state catharsis without the mohawked knuckle-dragging, owing far more to Charles Mingus and Max Roach than Johnny Rotten and Sid Vicious. I can't imagine this was the intention, but seeing his words here seemed to give affirmation to the angst of my teen years.

In what is sure to be the most controversial piece in the Biennial, Jordan Wolfson's virtual reality film Real Violence on the sixth floor was one of the most troubling works I have seen. Handed a pair of VR goggles and headphones by the museum staff, I was then instructed to hold onto the bar attached to the table for safety. The directions felt a little like those one gets boarding a roller coaster, and the experience was not dissimilar. Opening with a group of skyscrapers, my equilibrium was thrown off violently as perspectives changed and directions flipped repeatedly. I was relieved as the image sent me crashing to the ground, feeling as though I might become ill from dizziness. Unfortunately, things didn’t improve, just changed. What was waiting on the ground were a pair of men, one who immediately began crushing the other’s head with a baseball bat. No “Three Stooges” style slapstick, nor rubber prosthetic/Caro syrup horror movie violence. There were no obvious film FX cheats; the violence appeared sickeningly real and was made worse by lack of context. The camera never cut away. Removing the headset and stumbling into the next room, I took pause in the serenity of Asad Raza’s Root Sequence. Mother Tongue, a forest-like installation of 26 trees. A caretaker involved in the project engaged me in conversation about the species of trees, and it took me a solid minute to be able to actually converse with him and reorient myself. After I calmed down, I went back to watch people reacting to Wolfson’s video, spying sickly for a glimpse of their own revulsion.

I, no doubt like many others, expected this Biennial to be highly charged politically, given when it took place, and some might argue that it almost had a duty to be. Yet, while there are a very small handful of works referencing the current administration, one is never hit over the head with politics. We see so much more about the individual person and his or her role in today's society than we do simple antidisestablishmentarianism, crude effigies or anything of that sort. The political is here if you want it, but it requires introspection. A group of maniacally fun text-only video games by Porpentine Charity Heartscape come off like “Choose Your Own Adventure” books, albeit written by William S. Burroughs. The game I played had a sarcastic take on Capitalism, but not only is it enveloped in its own weird comedy, you're the one choosing to play its game. You're complicit in participation. With the best works of this Biennial, it's never a shouting match. There's no easy art here.

Most representative of the Biennial then, might be Another word for memory is life, the “non-signs” by Park McArthur. Possibly the largest-scale pieces in the exhibition, they're the most easy to overlook. The blank road signs fail at their only job, offering no direction as loudly as possible. They offer nothing more than volume, monoliths to locations never disclosed. Or maybe not. Maybe, like many of the artists here, eager for you to understand their world by participating with their art, that is indeed the political takeaway: the signs are empty because it's finally your turn. Instead of showing you the way, they're eagerly awaiting your direction, your story, to be placed upon them several stories high.

The Whitney Biennial 2017 runs through June 11. For further information, click here.

Image:

Installation view of William Pope.L, Claim (Whitney Version) (2017)

Collection of the artist; courtesy Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York.

Photograph by Matthew Carasella.