Three Relics of Abraham Lincoln

09/09/2021 Books & Autographs

NEW YORK, NY -- For many reasons, the powerful words and decisive actions of Abraham Lincoln have taken on new meanings today. This is particularly true of the Emancipation Proclamation, Lincoln’s most important act during the Civil War, which not only freed all slaves in areas seceded from the United States but changed the American citizenry forever. Three important items related to our 16th President are offered in Doyle's September 23rd auction, all of which resonate today.

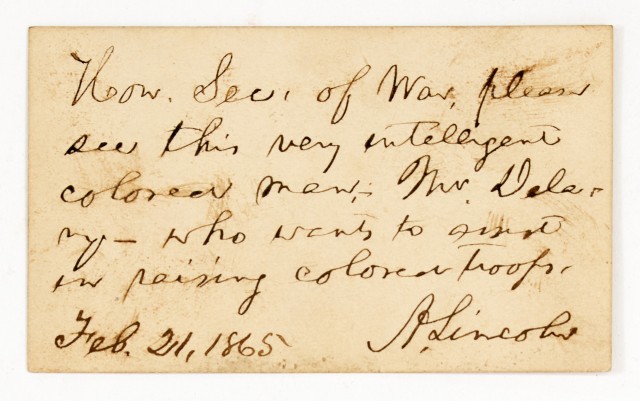

The first is a signed note in Lincoln’s hand dated February 1865, one of hundreds he would dash off during the Civil War on small cards or the back of a letter. But this note is particularly important as it changed history. Here Lincoln tells Secretary of War Edwin Stanton to “see this intelligent colored man, Mr. Delany - who wants to assist in raising colored troops” (Lot 36). While brief, the note was prompted by a historic meeting between Lincoln and Dr. Martin Robison Delany which resulted in his promotion to Major in the U.S. Colored Troops, becoming the U.S. Army's first Black field officer and achieving the highest rank of any African American during the Civil War. But Dr. Delany wasn’t just a military man, and his story has resonated and been reinterpreted in the over 150 years since this note was penned.

Born in 1812 to a free mother and enslaved father in Charles Town, Virginia (part of West Virginia after 1863), Martin Delany was raised and educated in Pennsylvania and, after an apprenticeship, opened his own medical practice. By 1842, Delany was publishing the abolitionist newspaper The Mystery and traveled to Rochester to work alongside Frederick Douglass in publishing The North Star. In 1850, Delany was one of the first three Black students accepted to Harvard Medical School only to be dismissed weeks later after complaints from white students. Feeling that Black people had no future in the United States, he authored The Condition, Elevation, Emigration, and Destiny of the Colored People of the United States, Politically Considered. By 1856 he had moved his family to Ontario, Canada, and there helped settle American refugees arriving from the Underground Railroad. In response to the passivity of some slaves in Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin, Delany wrote Blake; or The Huts of America, a serialized novel which chronicled the travels of a Black insurrectionist. In 1859, Delany sailed for Liberia to explore the possibility of a Black colony and was a central figure in a treaty with eight indigenous chiefs to create a settlement. The plans were dissolved partly by the coming of the American Civil War, and after 1861 Delany devoted himself to the emancipation of American slaves and the recruitment of Black soldiers into the Union Army.

In the war years before his audience with Lincoln, Delany was instrumental in recruiting Black troops to join 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment and served as its surgeon. His son, Toussaint L'Ouverture Delany enlisted in the 54th at 15 years old and survived the battle at Fort Wagner (memorialized in the 1989 film Glory). Due partly to Delany's efforts, 179,000 Black men enlisted in the United States Colored Troops, about 10 percent of all who served in the Union Army. In early February 1865, Delany traveled to Washington to convince President Lincoln that Black men would be more likely to join the Union Army if they served under Black commanding officers. An early biography recreated the conversation between Lincoln and Delany, and offers such memorable lines such as “You should have an army of blacks, President Lincoln, commanded entirely by blacks, the sight of which is required to give confidence to the slaves, and retain them to the Union' ... 'This,' replied the president, 'is the very thing I have been looking and hoping for; but nobody offered it; I hoped and prayed for it; but till now it has never been proposed.” With this note, handed to Delany by Lincoln, history was made as Delany was soon after commissioned the highest-ranking Black field officer in the Civil War, paving the way for generations of Black service men and women to come. As slight as Lincoln’s signed card may seem, it represents a pivotal moment in rapidly increasing inclusivity in the American military.

Lincoln’s meeting with Delany came in early 1865, just two months before his assassination, but earlier in the War Lincoln had issued his most important words of the conflict: the Emancipation Proclamation. In the auction is a beautifully rendered calligraphic broadside offering the text of the Emancipation Proclamation (under the highly decorative title Proclamation of Freedom) surrounding two watercolor portraits of Lady Liberty and Lincoln himself (Lot 38). Such presentations are rare and we trace several printed broadsides of this text at auction but no similar manuscript. A tour-de-force of 19th century American calligraphy, the importance of the text is matched by the elegance of the design and execution of the piece. When the Emancipation Proclamation became law on January 1st, 1863, 3.5 million enslaved African Americans in the secessionist Confederate states were freed and the country was forever changed. This manuscript memorializes that watershed moment. The broadside also has a notable provenance as it descended in the family of Union Army veteran Alexander Reed. As a Sergeant in the 90th Pennsylvania Infantry, in 1862 Reed saw extensive action over 90 days in the Battles of Cedar Mountain; Rappahannock Station; Throughfare Gap; Groveton & Gainesville; Bull Run; Chantilly; and South Mountain before being wounded by a bullet to the chest on 17 September 1862 in the Battle of Antietam. Active in the veteran's organization The Grand Army of the Republic, Meade Post No. 1 (for those who served under General George Meade), Reed was elected Commander in 1894 and as such was asked to perform the ritual of the G.A.R. over Ulysses S. Grant's remains at his funeral. It has been thought that this broadside was a gift for this contribution to Grant's funeral.

Finally, the legacy of Abraham Lincoln was cemented by the funerary procession that followed his assassination. Lavishly designed, the train car that became known as Lincoln’s Funeral Car was intended for the living President to tour the country but unfortunately was first put into service to transport the caskets of President Lincoln and his deceased son Willie from Washington to Springfield, Illinois in April 1865. A rare relic of Lincoln's funeral train is one of sixteen clerestory windows which served to ventilate the car (Lot 37). Crowds lined the tracks and many followed as the train took 12 slow days to reach Springfield. After its initial use, the train car had an interesting history and eventual demise. In 1866, in a great sell-off following the Civil War, the car was bought by the Union Pacific Railroad and brought to Omaha, Nebraska where it was used as a private car for directors. Subsequently sold and modified, the car was reacquired by the Union Pacific and was displayed in Omaha at the Trans-Mississippi Exposition in 1898. Sold several more times, the car eventually burned in a prairie fire in a Minnesota yard in 1911. A newspaper clipping accompanying the window pictures it alongside its original proud owner, Union Army veteran E.W. Kerr of Omaha, and it is very likely the frame was acquired there between 1870 and 1903. We trace another example of a clerestory window from the car in the collection of the Nebraska History Museum which also frames a late 19th century color lithograph of Lincoln, suggesting simultaneous assembly. Relics of Lincoln's funeral car are scarce and offer the opportunity to feel close to this great President in the days before his burial.

The fascination and reverence that Americans and the world feel for Abraham Lincoln grows as the years pass. These relics of Lincoln are great reminders of the remarkable acts of his days and the strength of his words.

Rare Books, Autographs & Maps

Timed Auction Closes Thursday, September 23, 2021 Beginning at 10am

Viewings by Appointment: Books@Doyle.com