Louise Bourgeois at MoMA

10/19/2017 General

NEW YORK, NY -- The exhibition “Louise Bourgeois: An Unfolding Portrait” recently opened at The Museum of Modern Art, and I was fortunate to attend a press preview. This is the third exhibition of the artist’s work at MoMA, and the most comprehensive presentation of her printed material to date. Like the earlier shows at the museum, it was curated by Deborah Wye, Chief Curator Emerita of Prints, who returned from retirement take on this important project. With around 300 works in total, the show presents 265 prints and illustrated books. Although most of us immediately think of Bourgeois’s sculptures when we hear her name, her prints in fact make up a large portion of her life’s work. I would encourage everyone to take this opportunity to see and appreciate her remarkable achievement as a printmaker.

Deborah Wye developed a working friendship with Louise Bourgeois, beginning in 1976, when Ms. Wye was an assistant in the drawings department of The Fogg Museum in Cambridge, Massachusetts. On one of her frequent trips to New York she was drawn to a Bourgeois sculpture in a MoMA exhibition, and then to another at a gallery, encounters that impelled her to learn more about the artist. Her research gave her little information, as there was not much published on Bourgeois at that time, so she arranged to visit the artist in her home.

Sponsored by the Fogg Museum, Wye secured a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts to conduct a year-long study of Louise Bourgeois’s art. When in 1979 Ms. Wye joined the staff at MoMA, she suggested organizing an exhibition of the works of Louise Bourgeois. Following on this, she mounted the first exhibition of Louise Bourgeois’s sculpture, including some drawings and prints, in 1982. This was followed in 1994 by a retrospective of Bourgeois’s prints. The artist also agreed to donate examples of each print to the museum, and Deborah Wye began the meticulous task of documenting her printed works in a catalogue raisonné. The complete raisonné is available online at www.moma.org/bourgeoisprints

Ms. Wye organized the current show thematically. I found this format very instrumental in emphasizing subtleties in individual works that I might have otherwise overlooked. Wye’s chosen themes are: Architecture Embodied, Abstracted Emotions, Fabric of Memories, Alone and Together, Lasting Impressions, Working Relationships and Spirals.

Bourgeois’ prints and sculpture often have architectural elements personified. Since she worked alongside European surrealists at Stanley William Hayter’s Atelier 17 in New York, it is understandable that her imagery is influenced by surrealism. Similar imagery can be seen in the works of American surrealists Atilio Salemme and Hananiah Harari, both born within a year of Bourgeois. But I would venture to say that her usage of architectural forms is more in line with Symbolism, as she is not drawing from the subconscious for random imagery, but rather makes use of symbols to represent people in her life. For example, since she admired the grandeur of skyscrapers in New York, in “Portrait of Jean-Louis” she depicts her son in the form of a skyscraper.

What I found most revealing in seeing this exhibition, and such a large overview of Bourgeois’s prints, is her extensive re-working of her ideas. Plate Seven from her nine plate book of prints titled “He Disappeared into Complete Silence” had eleven states. A state is the reworking of a plate before the final version of the print. Many artists will print a state to determine if further changes are necessary, and her use of states is quite frequent.

Another fascinating technique Louise Bourgeois used often is re-working a print with various drawing materials, thus creating a unique work amongst an edition of prints. Neither of these techniques are exclusively hers, but Bourgeois used these techniques at an alarming rate. Seeing her choices in the variations offers a window into her thinking that one solitary print could not.

Most of the exhibition is displayed in The Edward Steichen Galleries on the museum’s third floor. But visitors should be sure not to miss the large installation in The Donald B. and Catherine C. Marron Atrium on the second floor. This installation consists of large format prints along the surrounding walls, and at the center of the atrium sits a large spider standing over a wire cage. This cage has an empty chair within and fragments of old tapestries along the wire mesh of the cage. The door to the interior is slightly open, with a steel bar welded in place across the opening. It is documented that the artist saw her spider symbol as a representation of her mother, a tapestry restorer by trade. The weaving of tapestries and the weaving of a web are interchangeable in her mind. It is a haunting and magical installation.

Many of the works in this exhibition, and across Bourgeois’ entire career, depict figures, the human body, and her own self-portraiture. Her work delves into her personal struggles, putting them in public view in a very open, vulnerable way. This can be harsh, and yet inviting at the same time. And because there is a strong feminine quality to her subject matter, I expect this has long been part of why she did not gain greater recognition earlier in her career. But thanks to the inquisitive eye of Deborah Wye and a slightly less squeamish approach to feminist imagery, Louise Bourgeois now has a platform a great deal higher than she had at the outset of her career. Let us hope this exhibition brings even more attention to her artistic achievements.

Louise Bourgeois: An Unfolding Portrait

On view through January 28, 2018

The Museum of Modern Art

11 East 53rd Street

New York, NY 10019

MoMA.org

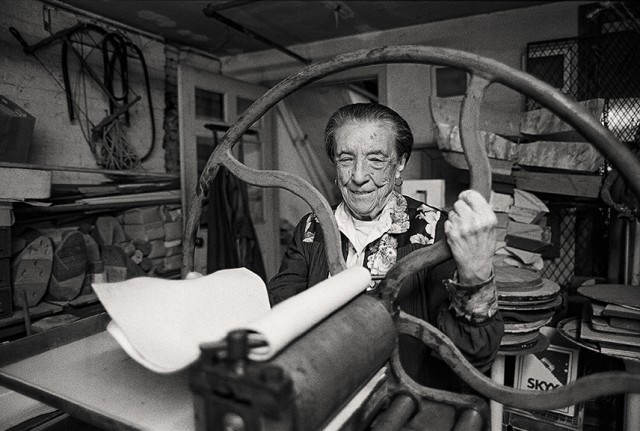

Image: Louise Bourgeois at the printing press in the lower level of her home/studio on 20th Street, New York, 1995. Photograph by and © Mathias Johansson