Folklore: The Enduring Legacy of Margaret Kilgallen

11/17/2020 Modern & Contemporary Art

“I am interested in things made by the human hand.”

– Margaret Kilgallen; artist statement from Three Sheets to the Wind, her 1997 Drawing Center exhibition.

NEW YORK, NY -- Much like the itinerant folk musicians of the 18th and 19th centuries that fascinated Margaret Kilgallen, the artist herself had a penchant for wanderlust. Following trains from town to town in between her exhibitions, Kilgallen had a passion for studying the local color, the tall tales and the everyday lives and pursuits of regular Americans. Rustic main streets of little towns with their mom-and-pop stores were ripe for exploration, all inspiration and fuel for her art. Growing up in Maryland, Kilgallen visited Amish farms in her youth and observed craftspeople making quilts, furniture, and painted signs by hand. These trips, as well as local fairs, flea markets and auctions provided glimpses into the folk traditions of the US. “I have always had an admiration for things that are well made, or not even well made. What you have to make in order to live,” Kilgallen explained.

A key figure in San Francisco’s Mission School scene, which also included Kilgallen’s husband Barry McGee, friends Chris Johanson, Rubi Neri and others, Kilgallen shared with the group a passion for surf and skate culture, punk and independent music, craft and folk art. While this assembly of artist friends all had varying degrees of studio instruction, they possessed a common fascination with the naïve arts and crafts – often made anonymously, this type of artwork retained its humanity, rough around the edges and honest.

The world was only given a scant few years to know Margaret Kilgallen. She passed away on June 26th 2001, having delivered her first and only child, Asha, just 19 days prior. At only 33, Margaret had succumbed to complications from breast cancer. To hear directly from her friends and family, Margaret’s was the flame that burned brightest. The tragedy of her death can sometimes eclipse how very vibrant and alive she was in life, the kind and noble friend she was, though this is clearly visible in her art. Margaret Kilgallen’s presence lives on through the power of her work, the inspiration it has and continues to provide.

Kilgallen’s work contains so many things we feel like we’ve encountered before; drawn from our own commonplace travels and experiences, everything adds up to a shared memory. At times, her work looks like a scrapbook featuring the objects and moments Kilgallen collected. Reconsidered, recontextualized, balanced, overlapping, stacked upon each other. These pieces of the past could have just as easily been sourced from the pages of a Faulkner novel as they could have been from a thrift store in Western Pennsylvania or a surf shack in the East Bay. Poetry can be found in the rhythm and arrangement of the seemingly random text that is scattered about her work – antiquated terms and forgotten nomenclature from earlier eras and clandestine pursuits – coupled with a color palette of bright reds and mellow greens influenced by Indian miniature paintings.

Kilgallen’s pursuits in letterpress and printmaking were crucial to her process; her work achieves a flatness altogether different than many of the Contemporary artists of her time who were intent on removing the artist’s hand, mimicking a product. Kilgallen’s take on “flat” was born out of a desire to emulate the look of a 19th century broadside, or a poster announcing a circus coming to town. Text, materials and ideas are sampled and re-employed with new purposes beyond their original reference. These anachronistic things no longer used, holdovers from prior generations. There are untold stories here, culled from the grit and emptiness of postwar towns after the boom had passed, places like Latrobe, PA or Bakersfield, CA where the streets lay silent, marquees for department stores and movie theaters announcing businesses long dormant.

Reinventing her exhibition spaces, Kilgallen would paint murals directly on the walls, adding on groupings referred to as “clusters” that combined sizes and mediums; works on paper were tacked to the wall next to painted wood panels and overlapping bits of found ephemera. Kilgallen developed a fascination with 15th and 16th century typography while repairing books for the San Francisco Public Library. In rebuilding these torn pages, she found beauty in the broken lines , one that carried over to her work: the pieces she sewed together, joined together, all busy and cluttered like the dusty corners of a used bookstore, begging to be explored. Layering and crowding in these clusters, drastically different than a normal salon style hanging, these spaces were intended to overwhelm. This is a reaction to, and a mimicking of, overstimulation in our modern society.

Barry McGee, Kilgallen’s husband, collaborator and travel companion, also embraced the cluster – not just in their shared exhibits but to this day as he shows new works in massive groupings, sometimes creating blister-like bubbles of layered works protruding several feet from the wall. The young artists shared a life together, albeit far too brief, living and creating, scrounging for materials, tagging freight trains. I am certain they made each other better artists and explored new ideas together as soulmates and collaborators, driving each other to create better work. To this day, Kilgallen’s artwork is included in each of McGee’s shows. Her spirit can also be felt when one views an exhibition of McGee’s.

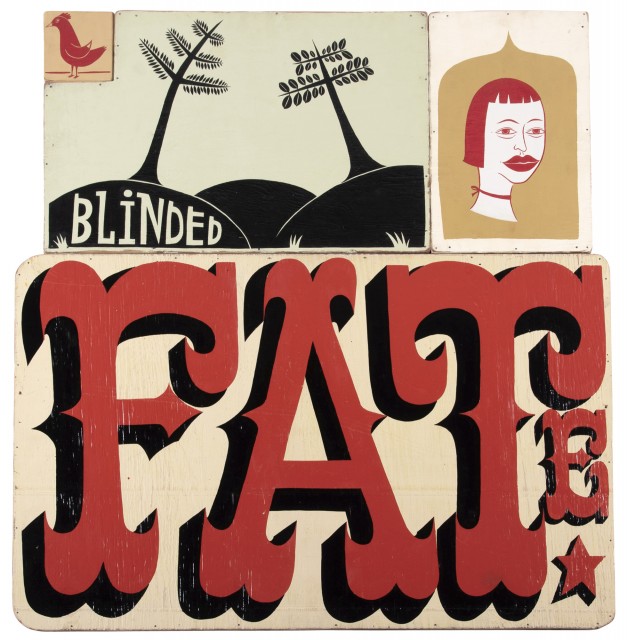

Consigned by the original owner, Untitled (Blinded Fate) from 1998 was originally purchased from the beloved Luggage Store Gallery, a non-profit arts space in San Francisco. The work was later featured in the 2005 CalArts Theater/REDCCAT retrospective In the Sweet Bye & Bye as well as the recent retrospective That’s Where the Beauty Is, both at the Aspen Art Museum, as well as the exhibition’s second stop at the Cleveland MoCA. The work is made up of four differently sized panels, clustered together but not attached to each other. Each wood panel has soft, rounded corners, with finishing nails running along the perimeter, as often seen in Kilgallen’s work. A little red bird is perched atop the upper left corner, like the tip of an antique weathervane. A portrait of a young woman sits at upper right, her head within a shape that recalls both an illuminated manuscript as well as the numerical flags that would pop up on the sort of brass cash register one might find at a soda fountain or general store. Enveloping the bird at upper left, the word “Blinded” sits within rolling black hills topped by silhouettes of two bending trees, the typography akin to what Kilgallen had employed periodically for her graphic design projects. Anchoring the bottom is the largest panel of the four, “Fate” with FAT in all caps and the little letter “e” shoved to the side. Her iconic red is propped up by a black drop-shadow, giving the letters dimension. These elements are not fragments that add up to a whole, but more a grouping of somewhat disparate objects, like a collection in a curio cabinet. When presented together, there is some cryptic narrative, some unknowable reason Kilgallen felt they belonged together, possibly recalling a moment or a memory.

In her famed PBS Art21 episode, Kilgallen studies a bodega sign she stumbled upon while exploring. She uses the piece to explain the marriage of art and utility. The person who created the hand-painted sign was not an artist and did not set out to make art – they simply needed a sign for their store and used what materials they could find, combined with what limited skills they may have had. The lines are perfectly imperfect, and from this comes the quote for which Kilgallen is most often cited; “…that’s where the beauty is.”

Like some other larger-than-life artists – Jack Kerouac, Frida Kahlo, John Coltrane to name a random few -- it’s hard to know where the art ends and the person begins, or if any such delineation exists. While her work is very personal, and at times precious and sentimental, Kilgallen was also a force. She lived with purpose and knew full well what behavior she would not accept from others. It has been rumored that her massive Deitch Projects mural of two women fighting, one wielding a broken bottle, was a tongue-in-cheek portrait of Kilgallen and her mother (who, of course, loved each other deeply). The artist lived and created in rejection of any elitism, always inquisitive, adventurous, supportive, overly generous and fully participatory in her community. Her patience was not meekness, but an uncompromising stoicism.

An unattributed quote from ANP Quarterly Magazine explains it succinctly: “Sometimes I’m amazed that in her short time on this planet she was able to leave behind so many gifts... Margaret’s not gone. She’s right here with us every day.” The unsung folk heroines Kilgallen loved and often reimagined within her work – banjo player Matokie Slaughter, Olympian swimmer Fanny Durack and several others – were inspirational for their unique skills, but also for the more ephemeral attributes they embodied: adventurous, independent women, bent on survival, tireless trailblazers yet still nurturing, kindred spirits from times past, heads full of dreams. I am grateful to know Margaret Kilgallen has become that same unyielding spirit for generations of young people everywhere.

Important Paintings

A highlight of the auction of Important Paintings on December 2, 2020 is Margaret Kilgallen's Untitled (Blinded Fate) from 1998.

Lot 47

Margaret Kilgallen

American, 1967-2001

Untitled (Blinded Fate), 1998

Acrylic on wood in four parts

41 1/2 x 39 inches (105.41 x 99.06 cm)

Provenance:

Luggage Store Gallery, San Francisco

Purchased from the above by the current owner

Exhibited:

Son of a Guston, Sep. 10 - Oct. 10, 1998, Clementine Gallery, New York

In the Sweet Bye & Bye, Jun. 16 - Aug. 21, 2005, REDCAT, Los Angeles

Margaret Kilgallen: That's Where the Beauty Is, Jan. 12 - Jun. 9, 2019, Aspen Art Museum, Aspen; traveled to: Museum of Contemporary Art, Cleveland, Jan. 31 - May 17, 2020

Literature:

Margaret Kilgallen: That's Where the Beauty Is, 2019, Aspen Art Museum, p. 62, p. 160 color illus.

Estimate: $100,000-150,000