Diaries of an American Master

04/20/2017 General

Gallery Walkabout / Saturday, May 6 at 2pm

Visit our exhibition of Impressionist & Modern Art and join Specialist Anne DePietro for an informal tour of works by Guy Pène du Bois from the Collection of Willa Kim and William Pène du Bois. Free and open to the public. No reservation required.

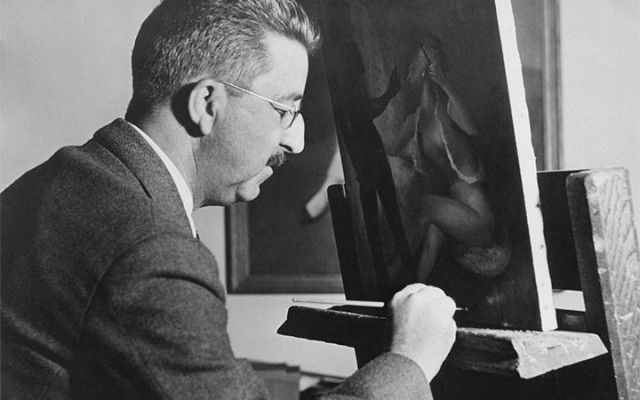

The Diaries of Guy Pène du Bois

On September 8, 1913, Guy Pène du Bois (1884-1958), an articulate and urbane bon vivant, made his first entry in a two-volume journal that for over forty years chronicled his daily activities: “A number of things are to be brought to account for the task I begin here – the building of a record.”

The diary documents his perpetual search for a living situation conducive to painting, his family life, and even his loneliness when his wife Floy and their children were away from him. In it the artist writes of his dual passions: writing and painting, and of his longing to practice one or the other when the opportunity to do so was limited. Although writing art criticism provided a steady income, it was truly something key to his existence, an activity without which he could not live. His language – even in a journal that at least initially was not intended to be read by anyone but himself – is elegant and fluid, and his writing flows effortlessly.

The journal begins as beautifully articulated daily reflections, but it is at times sporadic, and is even discontinued for an entire year. Without fail, however, it attests to chronic financial woes, which plagued Pène du Bois for much of his life, and resonate as a leitmotif throughout his entries. It reflects his enthusiasm for high and low culture, including the films and theatrical performances that he attended, his evenings with artist-friends and the exhibitions that he visited. He writes of visits with Floy to the race track and to Coney Island, destinations that did not further strain an overly-taxed budget, to observe the upper and lower classes at leisure. It was these experiences, informed with his acerbic wit, that culminated in iconic paintings such as Protectrice, Conversation on a Balcony, Bus Top, and other works from the Collection of Willa Kim and William Pène du Bois.

While Guy Pène du Bois attests in his first entry that he “shall write as little as possible, in this record, about art,” he immediately proceeds to contradict himself, writing with grace, even humor, about the work of his peers. Of George Bellows he writes that he “flys [sic] with no end of hurry from the beaches to the ghetto, from polo matches to prize fights, portraits to landscapes. He stops nowhere for any length of time. An hour at the night court produces a thing he calls a picture of it. Does it matter that he does not know it? Not a bit! He finds that the judge sits behind a counter dispensing justice like ribbons. He finds that girls, their beauty overdone, come before him to be condemned or freed with an unconcerned smile. He is interested by the picture again and that must be to him the surface. Our critics stand before it a moment, scribble a note and rush to their offices to proclaim, in their first edition – a genius!” [September 10, 1913]

In one of Pène du Bois’s most poetic passages, he writes, “Paint to the painter is more luxuriant than life, more luxuriant and more sensuous…. The impressionists… have given us a new harmony and a new song. Monet, dwelling upon the air and in it, has subjugated the material. He is to me, if this is not stretching a point, a frantic classicist. And yet I do not know that this is a good classification – his love of air verges upon the sensuous – he feels its motion, its color, its loveliness…. Monet’s intoxication uproots his feet until he walks on thin air, or rather, floats surrounded by wraiths that move with him, this way and that, in an ambient and wilful [sic] atmosphere…. Monet’s world is peopled with spirits. They are fed upon air and robbed of substance by air. They have no vices because they have no appetites.” [September 12, 1913]

The journal reflects the Pène du Bois family’s periodic moves to new locations: to Saugatuck, Connecticut in the summer of 1921, to Paris in late 1924, and back to America in 1930. With each relocation, Guy hoped to escape distractions, but each location presented new friends, new opportunities, and new distractions. In Paris, Guy rented a studio from the writer Ford Madox Ford (the family divided its time between Paris, the village of Garne in the Chevreuse Valley, summers in Villerville-sur-Mer, and, toward the end of their sojourn, in the south of France). He socialized with Mahonri Young and Paul Manship, visited with Leo Stein, and was an active participant in the cosmopolitan cultural milieu in Paris between the Wars. Guy and Floy dined at Café Dôme and attended the races at Longchamps.

While begun as a project to occupy the writer, Pène du Bois himself came to realize early on that his diary would be read – perhaps, even, that he intended for it to be read since the writing in it is so formal and he “very seldom… descend[ed] to colloquialisms [sic].” [May 11 1926] For us today to read his journal is to gain insight not only into his work, but into the vibrant transatlantic art world that he so enjoyed.