Charles White: Artwork as Activism

05/09/2023 Modern & Contemporary Art

NEW YORK, NY -- Born and raised on the South Side of Chicago, Charles White developed an early passion for reading and a great aptitude for the arts. He spent many hours at the public library, sadly, as White’s family was unable to afford child care, and would deposit him there to study and read unattended. The New Negro, the famous African American anthology edited by Alain Locke, was the discovery that provided White with the knowledge that African Americans had contributed abundantly to history, science and the arts. This was all knowledge White did not receive in public school, and he was even denied the possibility of adding it to the curriculum when he pressed his teachers. White would also hide his growing love for art from his fellow students, for fear of being bullied. Using any materials he could find, White would spend hours sketching while visiting the Art Institute of Chicago. White’s efforts would not go unnoticed, as he would later receive a scholarship to the School of the Arts Institute, joining an illustrious program that would see a remarkable number of stellar graduates in future years: Nancy Spero, Leon Golub, H.C. Westermann, Jim Nutt and Elizabeth Murray just to name a few. Two others academies offered scholarships, though they were rescinded when learning of White's race.

Joining Indiana’s arm of the WPA and producing murals throughout the late 1930s and into the '40s, White became obsessed with the Mexican Muralists: Diego Rivera, David Siqueiros, Jose Clemente Orozco and Rufino Tamayo, among others. This was art White felt one could touch, could represent a community. One did not need to be wealthy to see and experience it. The Mexican Muralists, and later, the WPA murals showcased laborers and addressed social issues. This was also what White drew from Kathe Kollwitz, whose work further impressed upon White to pursue images that document and champion the worker and their worldview. Eschewing abstraction during its zenith, White focused on representational work, a practice that would span his entire life and career.

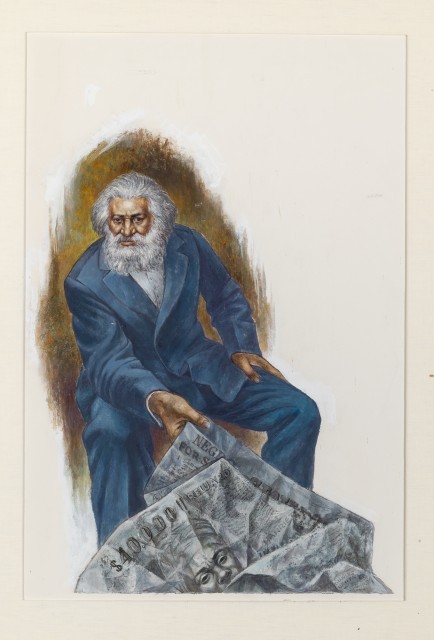

From 1965, Freedom Soldiers (Frederick Douglass with Wanted Poster) feels like a study for a mural, though by this period, the majority of White’s murals had long been produced. Douglass, the famed leader of the Abolitionist movement, is depicted in White’s unmistakable style. Douglass’ hands are as detailed and expressive as his face, something common to White’s work – deliberately rendered, slightly oversized, White’s hands speak to work and struggle. White’s figures radiate energy and determination, his hands as expressive as his faces. Possibly too late to be part of a Charles White mural, the work is also created just before White’s famed “Wanted Poster” series that would evolve just a few years later. As such, Freedom Soldiers may hint to the researching White may have been exploring at the time. With the Wanted Posters, White depicted images of anonymous figures enmeshed within these runaway slave posters, cruelly documenting their worth in US dollars, wealthy landowners looking to reclaim these human beings as if they were no more than a lost bicycle. These wanted posters are shown here in Freedom Soldiers emanating from Douglass’ hands and floating towards the viewer, rendered with the creases and inflammatory text that would become essential to White’s series to come.

Relocating to New York and attending the Art Students League, White would later meet then rising star Harry Belafonte in Harlem. The two worked together to change the perception of African Americans in the arts and entertainment. By 1957, Belafonte had commissioned White to create a portrait, capturing the performer in song. Belafonte then used this image to open his landmark television special in 1959, on CBS - an incredible rarity for its time. Belafonte would later pen the forward to Images of Dignity, White's first monograph. Like Belafonte, White was a key figure in the Civil Rights movement, earning himself a 300-page FBI file, spanning 1953-1967.

As notable as his artwork and activism, for Charles White, teaching was also essential to his work and practice. As a professor at Otis, White would teach a number of great artists of future generations: Alonzo Davis, Gary Lloyd, Judithe Hernández, Richard Wyatt, Jr., Ronnie Nichols, Kerry James Marshall, David Hammons, and many others, who knew White simply as "Charlie.” Passing away at only 61, White would teach at Otis through the end of his life, and provide a pathway for these next great artists to travel. “How do you know who you are?” was a question White would ask his students, challenging them explore not only themselves but their ancestry and history. White’s classes showed his desire for students to be more than just visual artists; to be intellectuals, to pursue knowledge, to challenge authority, to keep growing and learning. White felt that artists had a need and a responsibility to provide commentary on their society. “I was there to open the door. I opened the door for you to go in,” a student claims White told him. Charles White, if only through a serendipitous moment as a child alone in a library, researched and discovered his own history – Frederick Douglass, Harriet Tubman, Sojourner Truth and many others – devoted his life and career to that history and its long climb towards peace, brotherhood and community.

Post-War & Contemporary Art

Auction Wednesday, May 17, 2023 at 11am

Exhibition May 13 - 15

Featured in the May 17 auction is Freedom Soldiers (Frederick Douglass with Wanted Poster) by Charles White.