May 1, 2024 10:00 EST

Rare Books, Autographs & Maps

270

Thomas Jefferson expresses fears of "a war of extermination" in Saint-Dominigue

JEFFERSON, THOMAS

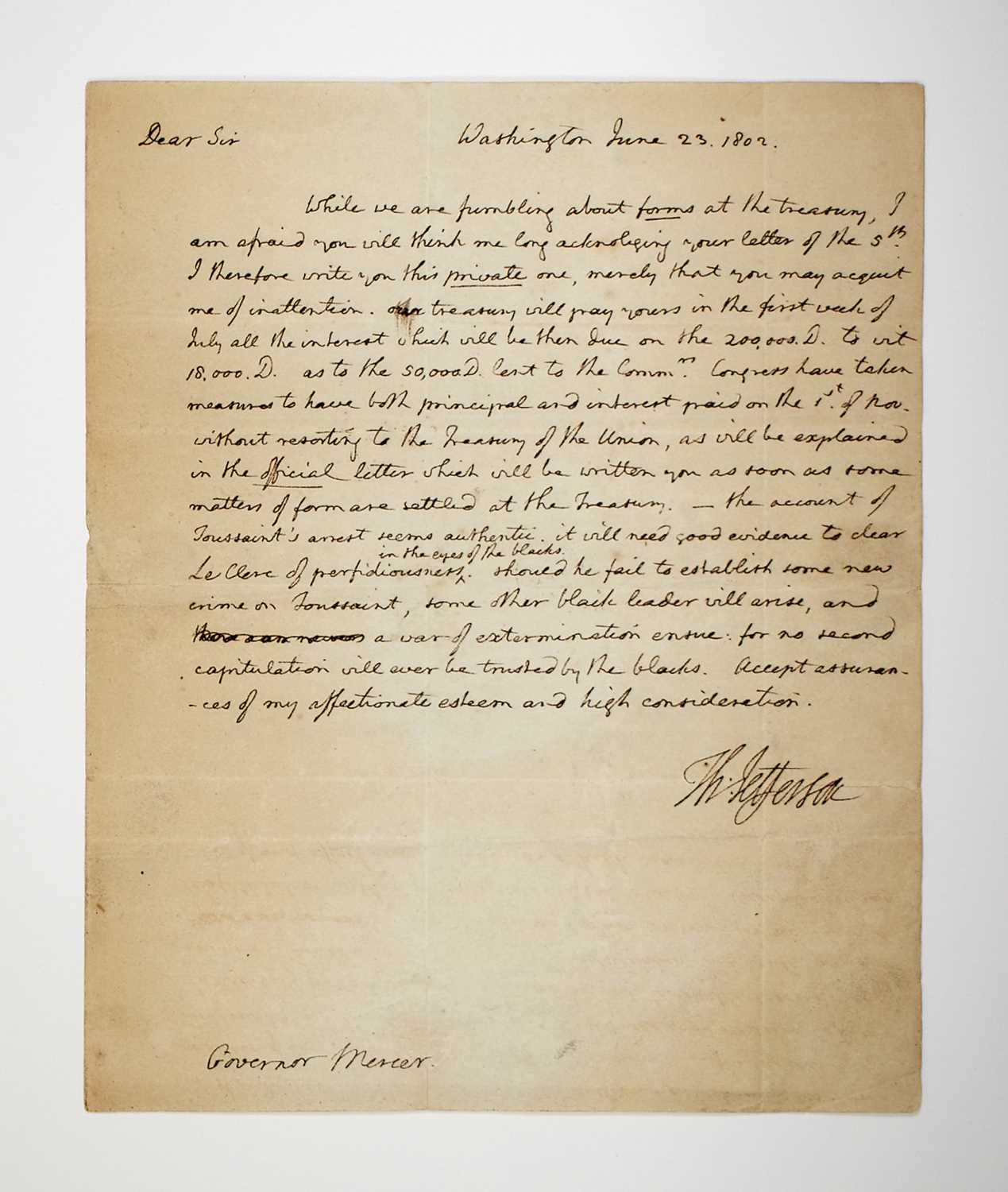

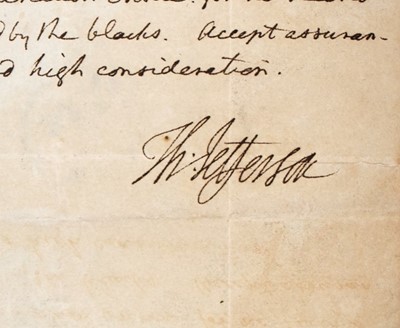

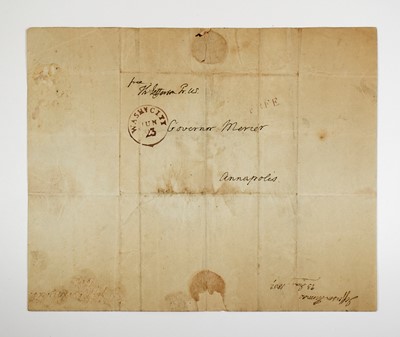

Autograph letter signed as President. Two pages on a single folded sheet of paper, letter dated Washington June 23, 1802, addressed to Governor Mercer (i.e. John Francis Mercer). Housed in a folding cloth case, with a portrait laid in. 9 3/4 x 8 inches (25 x 20 cm); 16 lines plus salutation etc., the conjugate cover sheet retaining portions of Jefferson's seal, his addressing information ("Free/Th. Jefferson Pr. US" and "Governor Mercer/Annapolis" with his free frank stamps, dated Wash. City June 23; docketed in another hand of the period "Jefferson Thomas/23 June 1802." Usual folds and some minor creasing, some toning and soiling, small losses from opening in the area of the seal on the gutter margin of the cover leaf, old erasure of a docketing indication to one corner of that page.

Jefferson writes to an old friend about interest owed him by the Treasury, and offers dramatic news of the arrest of Toussaint Louverture by Leclerc in Saint-Domingue, expressing his fears that "a war of extermination will ensue." The present letter is listed on the Founders Online database at https://founders.archives.gov/?q=Recipient%3A%22Mercer%2C%20John%20F.%22%20Period%3A%22Jefferson%20Presidency%22&s=1111311111&r=2. In this exceptional letter by Jefferson, one of few extant mentioning the great Haitian leader, Jefferson writes "the account of Toussaint's arrest seems authentic. It will need good evidence to clear Le Clerc of perfidiousness in the eyes of the blacks. Should he fail to establish some new crime on Toussaint, some other black leader will arise, and a war of extermination ensue: for no second capitulation will ever be trusted by the blacks..." This is an extraordinary and insightful letter, accurately predicting the outcome of Leclerc's actions, and it contains one of the few extant comments by Jefferson from the period of his presidency on Toussaint Louverture and the affairs of Saint-Domingue.

At the time of the slave rebellion that began in August of 1791, the colony of Saint-Domingue (later Haiti), the French portion of the island of Hispaniola, possessed an enormous (and enormously lucrative) economic output that outstripped that of all other European colonies, including the entirety of the Spanish possessions in the Americas. The plantations of the island produced huge amounts of sugar, coffee, indigo, cacao, and cotton. Almost one in eight people in France were at that time involved in some fashion with the trade, sales and manufacture of goods originating from there.

This vast economic engine depended in its entirety on slave labor; the approximately eight thousand habitations, the plantations owned by the French and free blacks, employed nearly half a million slaves, primarily of African origin. The slave system was exceptionally harsh, even by the standards of the era, in the way that it was regulated, in part perhaps because of the extreme disproportion between the numbers of the enslavers and their slaves. This captive labor force was controlled by some 32,000 whites (predominantly French) and 28,000 free blacks.

Sickness was rampant on the island, especially in the form of yellow fever. Ironically, this was likely not endemic to Hispaniola, but had come in with the imported African population. Primarily a disease of tropical Africa, it was spread by mosquitoes feeding on sick slaves, and it was especially deadly to the white population of the island, who had no immunity to it. Yellow fever was to play a striking part in the events of the next few years.

The slave rebellion, when it came, was swift, bloody, and successful. By mid-September of 1791, some 1500 plantations had been burned, and 80,000 of the enslaved had actively joined the rebellion. Two French deputations subsequently failed to quell the violence. Complicating matters for the French was the Revolution then roiling France itself, and the outbreak of war with Spain, which controlled the adjacent portion of Hispaniola, Santo Domingo. In the hope of quelling the violence, which was rapidly engulfing the entire island, in mid-1793 decrees of general emancipation were issued for large parts of Saint-Domingue. This was followed in short order (February 1794) by the abolition of slavery throughout the French empire by the Jacobin government in Paris.

Against this complex backdrop—a civil war in which the great powers of the time, Spain and England, were attempting to advance their own ends—a free man of color, Toussaint Louverture (his last name was an appellation that he added in 1793; we shall call him Toussaint here) emerged as an astute and forceful leader. Initially siding with Spain, he subsequently worked with Étienne Maynaud de Bizefranc de Laveaux, the French Governor of Saint-Dominque, to defeat the Spanish. A figure of extraordinary charisma and acumen, Toussaint navigated the difficult political landscape of the region to bring about a measure of social and economic stability. He invaded Santo Domingo, and thereby brought the Spanish portion of the island under his sway. He considered himself loyal to France, with the proviso, of course, that France should remain an enemy to slavery. In March of 1801, concerned that Napoleon, now ascendant in France, would reimpose slavery on the French colonies, he appointed a constitutional assembly to draft a constitution to formalize abolition: "No slaves can exist in this territory, servitude is therein forever abolished. All men are born, live and die free and French" was its third article (In the original: "Il ne peut exister d'esclaves sur ce territoire, la servitude y est à jamais abolie. Tous les hommes y naissent, vivent et meurent libres et Français.")

This was how matters stood in Saint-Domingue when Thomas Jefferson assumed the Presidency of the United States on March 4 of that same year. Both his predecessors, Washington and Adams, had had to deal with the foreign policy conundrum represented by the island, and Jefferson addressed the situation much as they had, pragmatically and with realpolitik. Privately, though a slaveholder himself, he was open to the idea of emancipation, writing on February 5, 1799 to Madison, in another letter that addressed Toussaint and the rebellion that “against this [i.e. the danger of insurrection inspired by Saint-Domingue] there is no remedy but timely measures [gradual emancipation] on our part, to clear ourselves, by degrees, of the matter [blacks] on which that le[a]ven can work.” George Washington similarly had come to believe that an incremental approach to emancipation was essential. John Adams had gone so far as to engage in trade negotiations with Toussaint. Still, he had experienced a backlash from Southern slaveholders who feared a slave insurrection that would spread to North America, a precedent that unquestionably influenced Jefferson’s cautious approach.

Napoleon did not take the matter of the new Constitution of Saint-Domingue kindly, seeing in it an affront to France and his own power. He appointed his brother-in-law, General Charles Victoire Emmanuel Leclerc to the head of an army that was to seize the island. Leclerc landed at Cap-Français on Saint-Dominique in February 1802, with 43,000 men (including 19,500 soldiers) and a promise from Napoleon (who had already privately repudiated it) not to reimpose slavery. Toussaint suffered several initial defeats at the hands of Leclerc, but the latter suffered a strategic reverse at the battle of Crête-à-Pierrot, and by April of 1802 the forces of Leclerc and Toussaint were effectively at a standoff. On May 6, the two met in Cap-Français and agreed to a ceasefire. Toussaint then withdrew to one of his plantations near Gonaïves, but was shortly after seized and deported to France, where he died of pneumonia and mistreatment while imprisoned in the Fort de Joux in the Jura Mountains on April 7, 1803.

Though Leclerc was successful in bringing about Toussaint’s defeat and destruction, he succumbed first, dying of yellow fever on November 2, 1802. A large part of the French invasion force was similarly afflicted. According to Mathewman, when the French withdrew after 22 months, a mere 7,000 soldiers and sailors remained, though this extraordinary rate of attrition may have included battle casualties, defections and desertions. With the French now decimated by disease, the insurrection flared again under the rebel general Jean-Jacques Dessalines, who defeated their army under General Rochambeau at the Battle of Vertières on 18 November 1803. He became emperor of the now-renamed Haiti in 1805. ("Haiti" is the indigenous Taino name for Hispaniola.)

General Dessalines approached Jefferson after an incident in which an American ship, The Federal, was briefly seized by Haitian patrol boats. In a letter directed to the President dated 23 June, 1803, Dessalines apologized for this seizure, and extended an invitation for a resumption of commerce. Jefferson appears to have ignored this overture, likely in part because of the brutality of Dessalines’s regime (the British had sundered relations for this reason), but undoubtedly also motivated by fear of the political repercussions of any favorable response from the representatives of the slaveholding American South. It was not until 1862 that the United States finally recognized Haiti’s status as a sovereign nation. Napoleon did not mount a further expedition against the island, and indeed, with the sale of the French territories in North America to the United States in the Louisiana Purchase, he abandoned his imperial plans in the western hemisphere.

The recipient of the present important letter, John Francis Mercer (died 1821), was a Founding Father of the United States, a Framer of the Constitution (though he did not sign), and a Governor of Maryland between 1801 and 1803. He was at the College of William and Mary with Thomas Jefferson, graduating in 1775, and he later studied law under the direction and auspices of Thomas Jefferson, who was a political mentor to him. The two men remained close, exchanging at least a half-dozen letters throughout Jefferson's presidency.

JEFFERSON, THOMAS

Autograph letter signed as President. Two pages on a single folded sheet of paper, letter dated Washington June 23, 1802, addressed to Governor Mercer (i.e. John Francis Mercer). Housed in a folding cloth case, with a portrait laid in. 9 3/4 x 8 inches (25 x 20 cm); 16 lines plus salutation etc., the conjugate cover sheet retaining portions of Jefferson's seal, his addressing information ("Free/Th. Jefferson Pr. US" and "Governor Mercer/Annapolis" with his free frank stamps, dated Wash. City June 23; docketed in another hand of the period "Jefferson Thomas/23 June 1802." Usual folds and some minor creasing, some toning and soiling, small losses from opening in the area of the seal on the gutter margin of the cover leaf, old erasure of a docketing indication to one corner of that page.

Jefferson writes to an old friend about interest owed him by the Treasury, and offers dramatic news of the arrest of Toussaint Louverture by Leclerc in Saint-Domingue, expressing his fears that "a war of extermination will ensue." The present letter is listed on the Founders Online database at https://founders.archives.gov/?q=Recipient%3A%22Mercer%2C%20John%20F.%22%20Period%3A%22Jefferson%20Presidency%22&s=1111311111&r=2. In this exceptional letter by Jefferson, one of few extant mentioning the great Haitian leader, Jefferson writes "the account of Toussaint's arrest seems authentic. It will need good evidence to clear Le Clerc of perfidiousness in the eyes of the blacks. Should he fail to establish some new crime on Toussaint, some other black leader will arise, and a war of extermination ensue: for no second capitulation will ever be trusted by the blacks..." This is an extraordinary and insightful letter, accurately predicting the outcome of Leclerc's actions, and it contains one of the few extant comments by Jefferson from the period of his presidency on Toussaint Louverture and the affairs of Saint-Domingue.

At the time of the slave rebellion that began in August of 1791, the colony of Saint-Domingue (later Haiti), the French portion of the island of Hispaniola, possessed an enormous (and enormously lucrative) economic output that outstripped that of all other European colonies, including the entirety of the Spanish possessions in the Americas. The plantations of the island produced huge amounts of sugar, coffee, indigo, cacao, and cotton. Almost one in eight people in France were at that time involved in some fashion with the trade, sales and manufacture of goods originating from there.

This vast economic engine depended in its entirety on slave labor; the approximately eight thousand habitations, the plantations owned by the French and free blacks, employed nearly half a million slaves, primarily of African origin. The slave system was exceptionally harsh, even by the standards of the era, in the way that it was regulated, in part perhaps because of the extreme disproportion between the numbers of the enslavers and their slaves. This captive labor force was controlled by some 32,000 whites (predominantly French) and 28,000 free blacks.

Sickness was rampant on the island, especially in the form of yellow fever. Ironically, this was likely not endemic to Hispaniola, but had come in with the imported African population. Primarily a disease of tropical Africa, it was spread by mosquitoes feeding on sick slaves, and it was especially deadly to the white population of the island, who had no immunity to it. Yellow fever was to play a striking part in the events of the next few years.

The slave rebellion, when it came, was swift, bloody, and successful. By mid-September of 1791, some 1500 plantations had been burned, and 80,000 of the enslaved had actively joined the rebellion. Two French deputations subsequently failed to quell the violence. Complicating matters for the French was the Revolution then roiling France itself, and the outbreak of war with Spain, which controlled the adjacent portion of Hispaniola, Santo Domingo. In the hope of quelling the violence, which was rapidly engulfing the entire island, in mid-1793 decrees of general emancipation were issued for large parts of Saint-Domingue. This was followed in short order (February 1794) by the abolition of slavery throughout the French empire by the Jacobin government in Paris.

Against this complex backdrop—a civil war in which the great powers of the time, Spain and England, were attempting to advance their own ends—a free man of color, Toussaint Louverture (his last name was an appellation that he added in 1793; we shall call him Toussaint here) emerged as an astute and forceful leader. Initially siding with Spain, he subsequently worked with Étienne Maynaud de Bizefranc de Laveaux, the French Governor of Saint-Dominque, to defeat the Spanish. A figure of extraordinary charisma and acumen, Toussaint navigated the difficult political landscape of the region to bring about a measure of social and economic stability. He invaded Santo Domingo, and thereby brought the Spanish portion of the island under his sway. He considered himself loyal to France, with the proviso, of course, that France should remain an enemy to slavery. In March of 1801, concerned that Napoleon, now ascendant in France, would reimpose slavery on the French colonies, he appointed a constitutional assembly to draft a constitution to formalize abolition: "No slaves can exist in this territory, servitude is therein forever abolished. All men are born, live and die free and French" was its third article (In the original: "Il ne peut exister d'esclaves sur ce territoire, la servitude y est à jamais abolie. Tous les hommes y naissent, vivent et meurent libres et Français.")

This was how matters stood in Saint-Domingue when Thomas Jefferson assumed the Presidency of the United States on March 4 of that same year. Both his predecessors, Washington and Adams, had had to deal with the foreign policy conundrum represented by the island, and Jefferson addressed the situation much as they had, pragmatically and with realpolitik. Privately, though a slaveholder himself, he was open to the idea of emancipation, writing on February 5, 1799 to Madison, in another letter that addressed Toussaint and the rebellion that “against this [i.e. the danger of insurrection inspired by Saint-Domingue] there is no remedy but timely measures [gradual emancipation] on our part, to clear ourselves, by degrees, of the matter [blacks] on which that le[a]ven can work.” George Washington similarly had come to believe that an incremental approach to emancipation was essential. John Adams had gone so far as to engage in trade negotiations with Toussaint. Still, he had experienced a backlash from Southern slaveholders who feared a slave insurrection that would spread to North America, a precedent that unquestionably influenced Jefferson’s cautious approach.

Napoleon did not take the matter of the new Constitution of Saint-Domingue kindly, seeing in it an affront to France and his own power. He appointed his brother-in-law, General Charles Victoire Emmanuel Leclerc to the head of an army that was to seize the island. Leclerc landed at Cap-Français on Saint-Dominique in February 1802, with 43,000 men (including 19,500 soldiers) and a promise from Napoleon (who had already privately repudiated it) not to reimpose slavery. Toussaint suffered several initial defeats at the hands of Leclerc, but the latter suffered a strategic reverse at the battle of Crête-à-Pierrot, and by April of 1802 the forces of Leclerc and Toussaint were effectively at a standoff. On May 6, the two met in Cap-Français and agreed to a ceasefire. Toussaint then withdrew to one of his plantations near Gonaïves, but was shortly after seized and deported to France, where he died of pneumonia and mistreatment while imprisoned in the Fort de Joux in the Jura Mountains on April 7, 1803.

Though Leclerc was successful in bringing about Toussaint’s defeat and destruction, he succumbed first, dying of yellow fever on November 2, 1802. A large part of the French invasion force was similarly afflicted. According to Mathewman, when the French withdrew after 22 months, a mere 7,000 soldiers and sailors remained, though this extraordinary rate of attrition may have included battle casualties, defections and desertions. With the French now decimated by disease, the insurrection flared again under the rebel general Jean-Jacques Dessalines, who defeated their army under General Rochambeau at the Battle of Vertières on 18 November 1803. He became emperor of the now-renamed Haiti in 1805. ("Haiti" is the indigenous Taino name for Hispaniola.)

General Dessalines approached Jefferson after an incident in which an American ship, The Federal, was briefly seized by Haitian patrol boats. In a letter directed to the President dated 23 June, 1803, Dessalines apologized for this seizure, and extended an invitation for a resumption of commerce. Jefferson appears to have ignored this overture, likely in part because of the brutality of Dessalines’s regime (the British had sundered relations for this reason), but undoubtedly also motivated by fear of the political repercussions of any favorable response from the representatives of the slaveholding American South. It was not until 1862 that the United States finally recognized Haiti’s status as a sovereign nation. Napoleon did not mount a further expedition against the island, and indeed, with the sale of the French territories in North America to the United States in the Louisiana Purchase, he abandoned his imperial plans in the western hemisphere.

The recipient of the present important letter, John Francis Mercer (died 1821), was a Founding Father of the United States, a Framer of the Constitution (though he did not sign), and a Governor of Maryland between 1801 and 1803. He was at the College of William and Mary with Thomas Jefferson, graduating in 1775, and he later studied law under the direction and auspices of Thomas Jefferson, who was a political mentor to him. The two men remained close, exchanging at least a half-dozen letters throughout Jefferson's presidency.

Auction: Rare Books, Autographs & Maps, May 1, 2024

-

Auction of Rare Books, Autographs & Maps on May 1, 2024 Totals $1.2 Million

-

A Medieval Manuscript Rules of St. Augustine Achieves $102k

-

Consignments Are Currently Being Accepted for Future Auctions

NEW YORK, NY -- Competitive bidding at Doyle’s May 1, 2024 auction of Rare Books, Autographs & Maps drove strong prices and a sale total that topped $1.2 million, surpassing expectations.

Featured in the sale was a fascinating selection of early manuscripts that achieved exceptional results. Highlighting the group was a 14th century manuscript of the Rules of St. Augustine from an English priory that soared over its $8,000-12,000 estimate to realize a stunning $102,100. The Rule of St. Augustine is among the earliest of all monastic rules, created about 400, and it was an influence on all that succeeded it. Other notable results included a 14th century Etymologiae of St. Isidore estimated at $5,000-8,000 that achieved $51,200 and a 15th century Prayer Book of Jehan Bernachier estimated at $10,000-15,000 that sold for $28,800.

A first edition of John James Audubon's octavo Birds of America sold for $41,600, far over its $25,000-35,000 estimate. Published in 1840-1844 in seven volumes, the first octavo edition was the final Birds of America publication overseen by Audubon in his lifetime.

The Fred Rotondaro Collection offered rare books and manuscripts on a range of subjects touching the African American experience in the United States over three centuries. A first edition copy of Frederick Douglass’ 1876 speech at the unveiling of the Freedman's Monument in Washington realized $12,800, far exceeding its $3,000-5,000 estimate. A first edition of the first issue of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin from 1852 also achieved $12,800.

Highlighting the range of offerings from the Ken Harte Collection of Natural History was a first edition Richard Bowdler Sharpe’s beautifully illustrated monograph of Kingfishers, 1868-71, that sold for $14,080, doubling its $6,000-8,000 estimate. It was accompanied by an inscribed copy of the rare unfinished chapter on the anatomy of the kingfisher by James Murie.

We Invite You to Auction!

Consignments are currently being accepted for future auctions. We invite you to contact us for a complimentary auction evaluation. Our Specialists are always available to discuss the sale of a single item or an entire collection.

For information, please contact Peter Costanzo at 212-427-4141 ext 248, Edward Ripley-Duggan at ext 234, or Noah Goldrach at ext 226, or email Books@Doyle.com