George McNeil: After Abstract Expressionism

09/08/2020 Modern & Contemporary Art

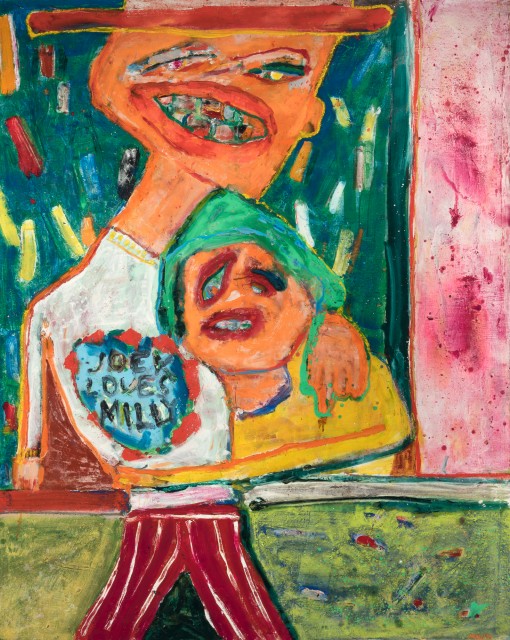

NEW YORK, NY -- Reviewing the 1984 Artist’s Choice Museum exhibition, George McNeil: Expressionism – 1954-1984, Michael Brenson of The New York Times singled out McNeil’s Joey Loves Milly for special praise. “In the 1977 Joey Loves Milly, the outrageous pinks, blues and greens – each of equal value – that are used to define the setting seem like the inner heat of a street scene in which a man in striped pants and hat is embracing his adoring, nestling woman. Everything in the painting is of a piece. In works like these, McNeil's color and distortions of scale bring to mind the richly human exaggerations of the Comedia dell'Arte. If he avoids the coyness that can accompany his kind of popular imagery, there is every reason to believe that McNeil's best work is still to come.”

Arriving at a laudatory review for this late period of McNeil’s work was a hard-fought, complicated road. George McNeil began in the 1930s creating Cubist works while simultaneously also painting abstractions. At the Art Students’ League, McNeil studied under Jan Matulka before moving onto a long mentorship under Hans Hofmann. In 1936 and 1937, Hofmann was not only teaching McNeil, but employing him as assistant, and as interpreter of Hofmann’s theories. McNeil would translate Hofmann’s decrees to his fellow students, who at this time included Lee Krasner, Giorgio Cavallon, Ray Eames and others, some of whom asserted they were really getting McNeil’s slant on Hoffman’s thoughts more so than a direct translation.

A first-generation Abstract Expressionist and part of the New York School, McNeil showed a predilection for pushing back against the status quo, sometimes to the detriment of his career. McNeil famously refused to be in the legendary 1951 “Irascibles” Life magazine photo, rebelling even against the rebellious, in a sense. And while art history has come to deify this group of eighteen artists; Rothko, Pollock, de Kooning, and others, McNeil took himself out of that picture, both figuratively and literally.

Similarly, as a founding member of the American Abstract Artists group, McNeil was again a prominent force, until departing for good in 1956 – he’d been slowly reducing his role there and eventually went his own way. Much like his friend and peer Philip Guston, McNeil found himself frustrated by what he saw as the limits of Abstract Expressionism and pushed for change. And much like Guston experienced when he debuted his own new body of representational work in 1970 to scathing reviews, the art world pushed back. American abstraction at mid-century, a movement McNeil was key in building, was violently opposed to the changes McNeil and Guston offered.

Throughout the 1960s, George McNeil’s work would grow more and more representational, though he largely retained the grand scale that he and his AbEx peers would implement – giant canvases with bold gestures. McNeil began a series of plein-air landscapes which now serve as a mid-point between his abstract work of the 40s and 50s and the cartoonish, figural paintings of which Joey Loves Milly is part. Building from a figural basis, McNeil endeavored to make his forms, as he described, “plastically and psychologically alive by having lines, shapes and colors bounce with energy.” This was not necessarily a new concept for McNeil, as he had long wished to explore the figure in greater depth, even going back to his formative time studying with Andre Lhote in France.

This representational period, beginning roughly in the early 70s and continuing through much of his remaining years until his passing in 1995 was dubbed Neo-Expressionism. Considering this term was simultaneously applied to the hottest young artists on the New York art scene in the 1980s, figures like Sandro Chia, Julian Schnabel and Eric Fischl, McNeil was by far the veteran of the movement. Yet to look at this period, it’s easy to imagine McNeil’s late works standing alongside Basquiat, Salle and this youthful crew – there is a shared future/primitive aesthetic; the works are reminiscent of de Kooning’s abstracted "Women," yet also show the influence of Dubuffet as well as CoBrA artists such as Karel Appel and Asger Jorn. McNeil was documenting NYC culture; disco, punk, graffiti – loud traffic, grimy clubs, bizarre characters. And even with such seemingly crude, stylized figures, so removed from AbEx, Hans Hoffman’s influence is still very present – particularly the vibrancy of the color palette, the rawness of expression. McNeil’s notoriously thick impasto providing depth and power to these toothy, contorted figures.

Like the city of New York during this time, McNeil chronicled the inherent anxiety and tragedy, but the screaming yellows and garish oranges add a comic strip pathos to the denizens of his world. Joey and Milly may be the wretched refuse of a city President Ford told to “Drop Dead,” but they seem jubilant within the chaos. George McNeil evidently echoed this same exuberance, stating in the catalog for the “Expressionism” exhibition in which Joey Loves Milly appears, that “I feel that I am just beginning to get a grip on pictorial excitement and extending the power of my abstract figurations.”

Important Paintings

Featured in the September 17, 2020 auction of Important Paintings is George McNeil's Joey Loves Milly.