Art of the Printed Book

04/20/2017 Books & Autographs

The middle years of the 19th century were a fertile time in typographical history, as new technologies for illustration and printing began to be incorporated into bookmaking. However, they were comparatively arid from a standpoint of fine printing in the tradition of the great 18th century printers such as Foulis, Baskerville and Bodoni. William Pickering, very much a commercial publisher issued typographically splendid books, but he was an exceptional case so far as trade publishing went. The so-called “parlor presses” flourished at this time, since small printing presses such as Holtzapffel's were widely available commercially, and whilst the output of it is fascinating to study and collect, there was little issued of literary or typographical quality, with the arguable exception of Gaetano Polidori's eponymous press of the 1840s -- he was a retired professional printer -- but his books have their enduring importance for the fact that he published the earliest works of Dante Gabriel and Christina Rossetti, who were his grandchildren.

The modern private press movement really began in 1874, when Dr. Charles Daniel, a fellow of Worcester College in Oxford, returned from his childhood home in Frome with a miniature Albion Press with which he had worked as a child. In Oxford, he chanced on the cases of the great type cut for Dean (later Bishop) John Fell at the Clarendon Press in the 17th century. He began to print with this splendid face in 1877. By 1880, Walter Pater was praising him in almost inordinate terms, "it is, I suppose, the most exquisite specimen of printing that I have ever seen." The press continued until 1903.

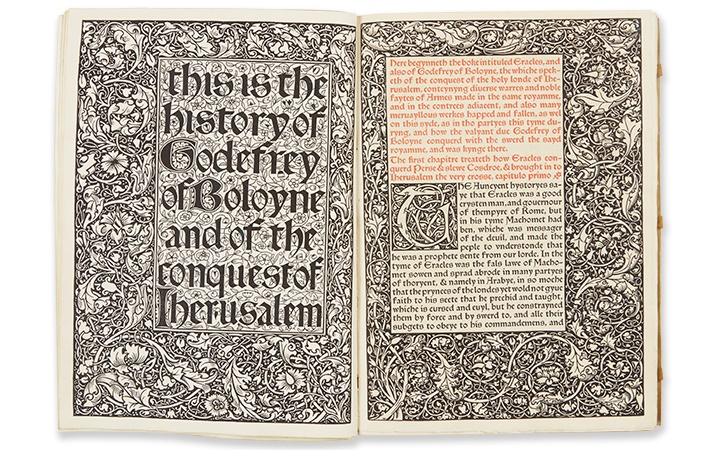

In 1891 William Morris established the Kelmscott Press from his home by the Thames at Kelmscott Manor. Morris was already recognized for his textile and wallpaper designs. He was a staunch Socialist, and was strongly influenced by Ruskin's doctrines on the dignity of work. In the earliest printed books, those of the 15th century of which he owned a significant library, he saw a nobility that he felt lacking in modern equivalents. He designed his own proprietary typeface (the first of three that the press was to use), called the Golden letter, based on the 15th century faces of Jenson (especially his Pliny of 1476). The first product of the press was his own The Story of the Glittering Plain, which would be the first of 53 books from his imprint. Although he died in 1896, the press continued with projects he had set in motion until 1898, under the stewardship of Sir Sidney Cockerell. The magnum opus of the press was the great Chaucer, illustrated with designs by Burne-Jones, with whom Morris had gone to Cambridge, and with whom he had been closely associated throughout his career. It is an amusing footnote, given Morris's Socialism (despite, or perhaps more fairly because of his espousal of that philosophy, Morris was extremely wealthy) that the Kelmscott Press was that rare creature, a profitable private press. Most have been run for love, not money, but Morris was a shrewd businessman.

Morris's success (artistic rather than commercial) gave birth to a host of presses in England, Europe and the United States. Fin-de-siècle aestheticism provided a rich and fertile medium for the private press movement. Lucien and Esther Pissarro's Eragny Press was among the most charming of these. Lucien, eldest son of the painter Camille Pissarro, together with his wife Esther, produced thirty-one titles, strongly influenced by Camille Pissarro’s pastoral vision, including an utterly ravishing wood-engraved books after Camille’s designs, La Charrue d'erable.

Charles Rickett's Vale Press did not do its own printing (that was done on a hand press on the premises of the Ballantyne Press, a very high-quality commercial establishment), but in all other regards it conformed to the private press norm. Ricketts designed three proprietary fonts for the use of the Press, and the books were generally illustrated by his wood-engravings, borders and initials (though several of the books bear illustrations by his partner, T. Sturge Moore). The type and matrices were destroyed after the termination of the endeavor in 1904. Ricketts was also involved with the Eragny Press; through the firm Hacon & Ricketts, which was established for the distribution of the Vale works, he also published some their earliest efforts.

Presses as diverse as C.R. Ashbee's Essex House Press and Cobden-Sanderson's austere Doves Press, two presses poles apart in their house style, all have their roots in the interest engendered by Morris's experiment and the Arts and Crafts ethos he inspired, though the Doves Press was in direct reaction to Morris's strongly decorative approach to bookmaking. Cobden-Sanderson, with Emery Walker the proprietor of the press, was a difficult, demanding and highly idealistic man. He was a great bookbinder and designer of bookbindings (the deluxe editions of the Kelmscott Chaucer were executed at the Doves Bindery). For all that he was capable of lush ornamentation in his bindings, he chose an austere approach to his printing. The typeface he designed (cut by Edward Prince, who was responsible for the realization of so many of the private press faces of the period) was also based on the Jenson Pliny that Morris had used as a model, but it was as if he had looked at an entirely different book.Where Morris's face was rather heavy, with comparatively short ascenders and descenders crowned with strong serifs, Cobden-Sanderson's version was much lighter in feel. All his books were printed in the same size of this letter. As Colin Franklin says, "This was of course a sign of great strength and assurance, a tour de force." The punches and matrices of this typeface ended up at the bottom of the Thames, for Cobden-Sanderson could not bear the thought of anyone else using them, even Emery Walker, his business partner in the press who had a commercial interest in them, an action that led to a breach of the friendship.

The Ashendene Press is chronologically the last of the great triumvirate of presses: Kelmscott, Doves, Ashendene. St. John Hornby's private press carried forward the idealism of the English private press movement into the 20th century. The first Ashendene book was printed in 1895; the last left the press in 1935. The life of the press spanned forty years, from Victorian England to the beginning of the modern era. It is tempting to see Mr. Hornby in the role of the last English gentleman; his correspondence reveals a courteous but extremely businesslike mind, as befitted a director of W. H. Smith's, the great firm of stationers. The Ashendene books show more stylistic range then most of the presses that originated in the ‘nineties. They range from the jewel-like vellum copies of the Song of Solomon to the magisterial folio editions of Boccacio, Dante, Malory, Thucydides and Spenser.

The private press movement in England did not end with the passing of the century. After the Great War was over and done, a new generation of private presses came into being. The Golden Cockerel, the Nonesuch, the Shakespeare Head, the Gregynog, all capably continued the tradition. In Europe, De Zilverdistel, the Cranach and Bremer presses, the Officina Bodoni of Hans Mardersteig and the Ernst Ludwig presses produced magnificent work long after Morris. The tradition continued then, and continues today, and probably will continue for as long as there are readers and lovers of books who understand that the printed book is more than the text it contains.

Rare Books, Autographs, Maps & Photographs / Auction Apr 26

The auction on April 26 offers a selection private press examples comprising lots 254 – 283.